THE HEALING WILDERNESS

by Melanie Reinhart

Sir Laurens van der Post describes how wherever the ancient people

known as the Khoi’San, the ‘Bushmen’ went, they felt known ...

"This sense of being known has completely abandoned us in the modern world, because we have destroyed the wilderness person in ourselves and banished the wilderness that sustained them from our lives. And because of the absence of the wilderness person in ourselves, we are left with a kind of loneliness, an inadequate comprehension of what life can be. We have become the greatest collection of know-alls that life has ever seen. But the feeling that our knowing is contained in a greater form of being known has gone."(1)

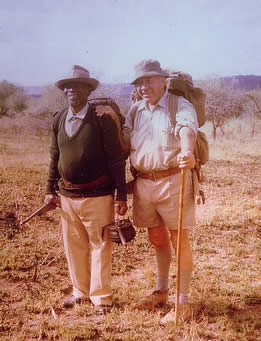

In July 1988, I had the privilege of participating in a wilderness trail in the Umfolozi Game Reserve, KwaZulu, South Africa,

with Dr. Ian Player (1927-2014) and Magqubu Ntombela (+-1901-1995).

This article is dedicated to the memory of these two great men.

Dr. Ian Player died peacefully at his home on November 30th 2014, noon EET.

I was born and bred in Zimbabwe, and spent a lot of time in the wilderness as a child, with my father who was deeply knowledgeable about African flora and fauna. He introduced my sister and I to the wilderness paradise that was this country. We used to practice our 'numbers' by counting wild animals! Decades later, on trail in KwaZulu, these words of Sir Laurens van der Post took on a new dimension of meaning for me as I listened once again to the symbolic and metaphorical language of the wilderness. Africa is surely the ‘Cradle of Mankind’, calling us to return to the stillness of our beginnings.

There were three others on trail apart from Magqubu, Ian and myself: Ingrid, staff member of the Wilderness School; Tracy, graduate psychology student from Cape Town; and Bob, a businessman from Nevada.

After entering the Reserve, we packed rucksacks with supplies and assembled for instructions before hiking to our base camp. The Umfolozi abounds in game, including predators and other potentially dangerous animals, and one must be mindful that it is, after all, their territory. We were to walk in single file, in silence, and to obey instantly any signals to back off, duck down, or run. Ian explained that an animal will not usually attack unless wounded, with its young, or if startled. Closer than ‘critical distance’, however, an animal may attack in self-defence.

‘Just like people’, I thought.

Ian continued, explaining that should we encounter any real dangers, our survival instincts would take over.

I struggled with the stomach strap of a weighty rucksack.

‘Don’t fasten that’, said Ian. I looked up in surprise.

‘You need to be able to drop the pack and run if you have to’.

My gut lurched as I realised that on trail ‘there is no insulation from the oldest realities of Africa’, to quote the Wilderness Leadership School literature.

We set off, following Ian and Magqubu. After only a few minutes Magqubu halted abruptly, crouched and aimed his rifle. Ian signalled us to back off in a hurry. I made ready to discard my pack and flee. I could see nothing, but heard a fearful crashing to the right, only yards away. Although my body was pulsating with a powerful energy, I was totally calm, my senses alert. It was true. Instinct had taken over. We backed off and stood riveted in an electric silence.

Ian turned towards us and mouthed the word ‘Buffalo’. Then I saw it. A huge black beast crashed away from us, tossing its homed head. Another and another. They disappeared, and we silently resumed our walk. Buffaloes can be dangerous: they are very fast and one of the few animals that may charge on sight.

We arrived at camp, laid our ground sheet under the sky and arranged our ‘territory’. Dinner was cooked over an open fire, and night fell as we started our meal. Night always comes quickly in Africa. In half an hour or so, the brilliance and warmth of daylight retreated in a fiery display, as the red sun was engulfed by the horizon.

The temperature fell steeply. Millions of stars pricked through the indigo canopy that arched over us; soon a thin crescent moon emerged, shedding a cool silver light which seemed to cast oblique shadows through the trees. Ian pointed out the constellation of the Scorpion right overhead. As an astrologer, I was struck by this, for I knew that the next day there would be a station of the planet Pluto in the sign of Scorpio, a planetary event heralding the intensification of emotional experience, and stimulating the process of personal transformation through descent, death and rebirth. As Pluto is Lord of the Underworld in Greek mythology, I wondered what might emerge from his domain.

Every night on trail, each person had about two hours awake and alone, to keep watch, guarding the sleepers, and also for contemplation. I chose 2.00am-4.00am, my favourite time of night. Dozing in my sleeping-bag, I heard someone whisper ‘Scorpion!’

I sat bolt upright. An enormous khaki-coloured scorpion was dancing at the edge of the fire. It ran to and fro, as if in an ecstatic trance, and eventually Bob pushed it in.

‘Just like life’, I thought. ‘Dance too close to the fire and eventually you will get pushed in’.

I fell asleep thinking about Pluto, and soberly reflecting on how most of us try to destroy the wild ecstatic creature within us. I wondered if it necessary to push it into the fire. On the other hand, I was glad it was gone, although of course there could have been more such visitors! Was I, like the scorpion, about to be pushed into the inner fires of my own psyche?

During my night watch, the darkness teemed with invisible birds and animals, grunting, coughing, whooping and snuffling; some calls were hoarse and raucous, some mellow and melodious. Twigs cracked, leaves rustled and wings flapped in a tapestry of sounds mostly unidentifiable to me. I communed with the world of those who once lived there and it was as if I became the wilderness man, or rather woman. Tears flowed. Home at last.

I dream that a black rhino crashes into the camp in the dark. One woman panics, grabs Magqubu’s gun and we just manage to stop her shooting. Suddenly it is bright light and three men appear, walking quietly to work. I am confused. This wilderness is right on the edge of a city, or is it the other way round?

During the next day we walked for hours in silence, often passing sandy depressions where rhinos had rolled and deposited enormous droppings; a nearby tree had been polished shiny by countless animals rubbing against it, scraping off ticks and mud.

We followed narrow footpaths beaten by rhinos, the ‘path makers of the bush’. For millennia, the human inhabitants of the region have also used these paths, and their spirits seemed to endure. A timeless stillness would fall as we approached a burial site, marked by simple round stones. I felt I was participating in a kaleidoscope of life, travelling simultaneously through the animal, human and spirit worlds. Treading the rhino paths, I sensed an evanescent presence that would periodically break into kinetic images, a freeze-frame movie of invisible rhinos accompanying us through their territory. I felt myself enfolded within the soul of the rhino, and I thought about my dream.

We travelled through tangles of brittle beige grass and across dry riverbeds; a soft mauve haze shrouded the far hills and belied the sandy dryness underfoot. Here and there, lush new emerald grass shoots had burst through charred and blackened tufts created by a huge bushfire. Towards mid-afternoon, we circled back via the Umfolozi river. Recent animal traffic was etched in a profusion of spoor criss-crossing the sand; Ian and Magqubu could read them like words. An enormous crocodile sunned itself on a distant rock, surveying his river kingdom. Further up-stream from its habitat, we bathed in the cold shallow water. This was surely the Garden of Eden.

That night after dinner, there was an atmosphere of expectation. Nobody spoke much. I wondered about my dream. Then a prolonged splashing, sounding loud and very close in the night-time stillness...

‘Game crossing’, explained Ian.

‘The Animals emerging from the Underworld’, I thought to myself.

Activity increased in the darkness; many animals were arriving on our side of the river, perhaps escaping from predators. I stared into the flames of the fire, my eyes watering from the intense stinging smoke. As my vision cleared, I saw an incandescent head of a black rhino.

‘That log looks just like an animal head’, I said. I opened my mouth to say, ‘A rhino’, but heard instead a loud snort, apparently just behind me! The hairs on my neck rose like the hackles of a threatened dog.

‘Black rhino’, said Ian. ‘Close’.

I saw Magqubu’s rifle, propped up near him. All boundaries between inner and outer vanished and I melted into my dream. I sat in silent dread, my breath almost frozen. On the opposite side of the camp something else was now moving about noisily.

‘Buffalo’, said Ian.

I felt utterly surrounded; my mouth was dry and my heart pounded. The rhino circled around us, the silent darkness amplifying everything to a terrifying cacophony of crashing, snorting and cracking. We were told this meant a black rhino was browsing there: unlike the white rhino, a grazing animal, the black rhino will lean on young trees, bend and break them in order to reach the leaves. White rhinos are relatively passive, but black rhinos are notorious for their irascible nature, and may charge without provocation.

Magqubu’s eyes sparkled in the firelight. In a mixture of Zulu and English, he and Ian began recounting alarming tales of previous encounters with rhinos, on trails such a this one. Such was Magqubu’s knowledge of and rapport with animals that he could imitate perfectly their sounds and movements. He literally became a rhino, tossing his head, pawing the ground, snorting and laughing in accompaniment. Here at work was the archetypal function of story-telling. As the imagination is invoked and feelings intensified, personal experience becomes universalized as both story-teller and audience are opened to the numinous content within a situation. Almost as an aside, we were quietly told that if the rhino should actually charge, we were to run up a tree and stay there! An intoxicating blend of real and imaginary danger.

Needless to say, the solo night watch presented an awesome prospect. Tracy and I went to relieve ourselves before going to bed, but we were interrupted by an ominous loud rustling. A large unidentified animal loomed, very close! We fled back to camp, breathless. For me, this was the final straw that broke the back of my fear.

‘We saw something out there!’, I whispered breathlessly to Ian.

‘There’s a lot out there tonight’, he replied simply. I was on the edge of panic, afraid my dream would manifest. Should I tell it? Would it come true? Would I panic and grab the gun? Was this inner or outer or both?

‘I’m really afraid’, I confessed, feeling a bit ashamed. I told him my dream.

‘I think you must take it subjectively’, he replied, simply.

‘I’ve been doing that all day’, I responded feebly, thinking to myself ... ‘And now look what’s happening. So much for subjectivity’.

But his taciturn calm snapped me back into myself, gave me back my boundaries and my sense of trust returned. I went through a barrier of fear and stepped out the other side. I slept peacefully until just before my night watch, which passed without event.

The next morning, we made a stew of boerewors (2) and vegetables and carefully lodged the pot in the embers of the fire.

‘If the baboons don’t get it, there’ll be a delicious dinner waiting for us when we come home tonight’, said Ian with wry humour. Magqubu began animatedly scraping some burning coals into a circle around the fire, protecting our dinner from marauding, hungry baboons. He chuckled and chattered, now impersonating a baboon trying to get to the stew, getting his feet burnt, and leaping back with whimpers and loud shrieks. This hilarious scenario was re-enacted several times with relish, and we were all still laughing as we set off, following the rhino tracks.

‘We’ll see rhino today’, Ian said with the conviction of one whose intuitive sense has been sharpened over decades in the bush. We entered an eerie glade of charred and broken trees surrounding a cluster of shallow mud-holes. Rhinos had recently been there, and we were as trespassers in their sanctuary. Out the other side, visibility was limited and my hearing sharpened; the rhythmic brushing sound of us pushing through the tall grass was like music. We scrambled down a steep slope covered in vegetation and down to a sandy riverbank below. Preparing to cross the river was a deeply symbolic moment for me, a transition into another dimension of experience.

As we stepped in, I wondered if rhinos awaited us on the other side. Swirled by a fast current, the sand shifted under my feet. The water got deeper and colder; it slid over my knees and seeped into my rolled-up trousers.

We were following in the footsteps of countless creatures, human and animal, over millennia, which had crossed this threshold before us.

Finally, we clambered out on the other side, pausing to dry off in the sun before continuing.

Then time seemed to slow down and stop. I saw Magqubu take his hat off, and I thought he must have heard something. A quiet snort. Yes, a rhino. My eyes strained to see it. We backed round a clump of bushes into a more open area, having been signalled to keep down. Animals know the image of ‘upright man’, and so walking crouched down is less likely to startle them and make them run or attack.

We had a magnificent view of the rhino, an enormous mother with two young calves. Judging by her size, and also because we were allowed to get so close, I realised it must be a white rhino. She stared in our direction. Her horn was very long, unusually straight. I was transfixed, communing across the boundary of species; I imagined myself actually being this huge beast, and sank into the experience of life as a rhino.

Vitality flowed to and from the sandy earth in a pulsating throb of energy as I merged with the surrounding bushes. After a timeless few minutes, I came back to my human self, and the rhino eventually lumbered into the distance with her two little ones following, swinging her huge bulk with slow rhythmic grace.

‘The rhino must be the unicorn of Africa’, I thought. I remembered a phrase from the Bible: ‘The strength of God is like a rhinoceros’. The unicorn is another image of the strength of the Spirit that penetrates all life, but can also impale and kill; it may be wild and capricious and can only be tamed by a pure virgin, or woman whole in herself. The unicorn is a product of man’s imagination, but the rhino is a real animal, perhaps symbolizing the vital drive within the ‘body of mankind’. Communing thus with it, I had felt in touch with the Spirit of Life as a whole.

The rhino we had seen was a female. It reminded me of ancient clay figurines of a fertility goddess, depicted with both breasts and a penis. The active principle of the feminine, well represented in the Hindu pantheon by figures such as Kali and the Mahavidyas, has no parallel in Judeo-Christian iconography. I was reminded of another rhino dream from a previous trip to Africa, about a year before ….

A black rhino is imprisoned in the house of my grandfather, snorting wildly and trying to get out. I know I will be done for if it does. My father appears, saying we should get a gun with some tranquilizing darts.

Reflecting on the rhino I had just seen, it occurred to me that perhaps the real danger was the ‘tranquilising father’, whose image of woman is of someone docile, compliant and existing to obey others. I reflected on the extremes of rebellion that this had provoked on my quest to find myself, and I felt a sense of excitement that my ‘rhino self’ was no longer imprisoned in ‘the house of the father’.

That night, staring again into the fire, very aware of the fragility of human consciousness, embedded in the totality of life. Inside the magic circle of the campfire, circumscribed by magnificent old logs and rhino skulls, one felt safe from the primordial darkness outside. I imagined our human ancestors sitting thus, perhaps enjoying the same illusion of safety. The fire came for me to symbolize the core of individual consciousness, and the ring of seats its field of awareness. Beyond lay the dark unknown, the plenitude, full of wonder and terror and numinosity.

I dream of a wilderness I never knew before, that I can always walk into. It is right next to my flat in London, green and very lush, with pine trees growing in it. I feel awed and refreshed.

Tracy roused me for the watch. I had settled into some writing when there was a loud volley of the now familiar cracking sounds. Another rhino. A very large animal was indeed browsing enthusiastically out there, and moving closer, too. I sprang to my feet, involuntarily, but decided not to raise the alarm yet. Suddenly, a blood-curdling shriek from the trees above. I started as if I had been shot, then smiled. I recognized the sound of a ‘bush-baby’, a tiny, furry creature with big appealing eyes and a long curly tail, like a Walk Disney cartoon of the ultimate ‘cute’ animal.(3) Yet from its tiny mouth issues a spine-chilling sound, as if some monstrous underworld entity is intent on ‘getting you’ if you don’t die of fright first! The bush-baby seemed an apt symbol for the wildness of Africa, perhaps of life itself, where things are often not as cute and furry as they might seem. The humour seemed to break some kind of spell, and the rhino moved slowly away, leaving a black void of deep silence behind.

I dream that my grandfather gives me a watch, and another gift. My grandmother presents me with a beautiful ornate belt made of animal fur, old leather and gunmetal …

The grandfather in whose house the rhino had been imprisoned in the previous dream is now giving me a watch. I associate the watch with Father Time, Saturn, with the laws of manifestation, creativity in real terms. A positive masculine image, for me. The belt reminded me of the potentially destructive gun of my recent dream, but here fashioned into an ornament, a gift from a female ancestor. I think of famous girdles in Greek myth ... those of Aphrodite and Hippolyta, the Amazon Queen. Both express independent feminine strength and creativity, one sensual and receptive and the other active and competitive. My grandmother seems to be offering me these attributes. I say a prayer of thanks on waking.

It was now the last morning, a poignant moment. The fire area was swept clean, no longer providing a welcoming focus for the group.

We met for the final indaba, an opportunity to express what the trail had meant to each of us. Such was the lump in my throat that I could barely speak. Tears rolled down my face as we hiked silently back to the van.

I felt like Everyman on a sorrowful journey, cast out of Paradise and doomed to a long quest to return. I prayed to the Spirit of Umfolozi to protect me and help me follow the thread of my rhino dream. To help me ‘watch’, a pun on the one I was given …

We drove into the shocking bustle of Durban, and went our separate ways. I felt forlorn as I entered my hotel room, with its gleaming brass lamp-stands and white marble bathroom. I sat on the floor in my dirty trail clothes until dark. I did not even remove my hat. I did not want to wash the wood-smoke from my hair, nor the soot from under my finger nails. I wanted to smell this way forever, to carry the soil of Umfolozi everywhere with me.

A song by Johnny Clegg came to me:

‘We are scatterlings of Africa, each and every one,

Scatterlings of Africa on our journey to the Sun’.

Next morning I completed the transition back to ‘civilization’; I put on make up and city clothes and departed. But the rhino seemed to follow me. At Johannesburg airport, I saw a beautiful wooden bangle made from ntomboti wood. This wood is very hard, burning hot and long with a distinctive and ominous smell, faintly sickly and a little intoxicating, a smell that will forever infuse my memories of night-time on trail. The fumes from burning ntomboti will make you ill if you cook over it, but the wood is used as a love charm by traditional Zulu herbalists — Aphrodite again! The leaves and supple young branches are a favourite food of the black rhino, and some say this accounts for its belligerent nature — like the Amazon. I put on the bangle, silently telling my ‘inner rhino’ that this wood, from her favourite tree, was her lunch.

A week later, at the mysterious ancient walled city of Great Zimbabwe, I came across a beautiful soapstone carving of a black rhino, which I bought and carried carefully back to London. It watched over me for many years while I slept and, indeed, the Spirit of Umfolozi has brought many dreams that continue to unfold the meaning of this return to and from my origins.(4)

_______________________________

ENDNOTES

(1) Van der Post, Sir Laurens, "Wilderness, A Way of Truth”, essay in the anthology "A Testament to the Wilderness", ed. CA. Meier, Daimon Verlag, Zurich, 1985.

(2) Boerewors is a spicy sausage, a traditional South African delicacy. The word means ‘farmer’s sausage’.

(3) ‘Bush baby’ or naagapie (night-ape) in Afrikaans. Click here for information, and here for picture gallery.

(4) Almost 20 years after this piece was written, and having relocated to a small village north of London, I discovered that the (paternal) grandmother who appeared in the dream recounted above had been born and baptized just north of where I now live. Guidance from my mother’s spirit led me to find this information, which was previously unknown by her children (including my father) while she was alive. Her origins were a complete mystery, couched in ‘family mythology’ with few facts known.

On discovering this, I decided to perform a variation on the traditional African ceremony of ‘bringing the spirit back home’ for which the eldest child is responsible. If someone dies a long way from where they were born, the spirit must be returned to the place of birth, or it is believed that it might remain unquiet. My dream of the black rhino imprisoned in the ‘house of the father’ can therefore also be seen to refer to the unquietness of spirit perhaps felt by this grandmother. She always spoke longingly of the ‘green fields of England’, and it was deeply touching to be able to ‘bring her home’ to the very fields of her naissance. The black rhino carving mentioned in the final paragraph, above, was guarding the door of my house until this point, when it felt like ‘mission complete’.

Prior publication:

- ‘Link Up’ magazine, UK, Summer 1989, Issue 39.

- Anthology ‘Wilderness and the Human Spirit’, Cameron Design, Cape Town, 1997. ISBN 9780620201438. A fund-raising project of the Wilderness Foundation.

Revised December 2014.

(Minor edits, re-formatting, addition of endnote 4.)

Photo credits: Melanie Reinhart, Dr. Ian Player